Cougar

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with United States and Canada and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2012) |

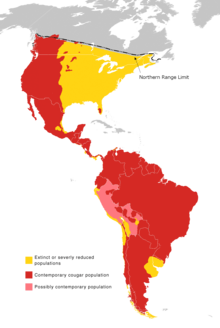

The cougar (Puma concolor), also commonly known as the mountain lion, puma, or catamount, is a large felid of the subfamily Felinae native to the Americas. Its range, from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes of South America, is the greatest of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere.[3] An adaptable, generalist species, the cougar is found in most American habitat types. It is the second heaviest cat in the New World, after the jaguar. Secretive and largely solitary by nature, the cougar is properly considered both nocturnal and crepuscular, although sightings during daylight hours do occur.[4][5][6][7] The cougar is more closely related to smaller felines, including the domestic cat (subfamily Felinae), than to any subspecies of lion (subfamily Pantherinae),[8][9][10] of which only the jaguar is native to the Western Hemisphere.

| Script error: The function "speciesboxName" does not exist. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cougar | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template ([[[:Template:Create taxonomy/link]] fix]): | [[Template:UnstripNoWiki]] |

| Species: | Template:Taxon infoTemplate:Taxon italics |

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxon infoTemplate:Taxon italics (Linnaeus, 1771)

| |

| Subspecies | |

Also see text | |

| |

| Cougar range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The cougar is an ambush predator and pursues a wide variety of prey. Primary food sources are ungulates, which include deer, such as mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, and moose, other ungulates it preys on are bighorn sheep, as well as domestic cattle, horses and sheep, particularly in the northern part of its range. It will also hunt species as small as insects and rodents. This cat prefers habitats with dense underbrush and rocky areas for stalking, but can also live in open areas. The cougar is territorial and survives at low population densities. Individual territory sizes depend on terrain, vegetation, and abundance of prey. While large, it is not always the apex predator in its range, yielding to the jaguar, gray wolf, American black bear, and grizzly bear. It is reclusive and mostly avoids people. Fatal attacks on humans are rare, but have been trending upward in recent years as more people enter their territory.[11]

The cougar population sharply declined due to hunting and habitat loss during European colonization, leading to extirpation in eastern North America by the early 20th century, except for a surviving subpopulation in Florida. Recent decades have seen the reestablishment of breeding populations in the far western regions, and despite being declared extirpated in 2011, reports of eastern cougars persist, suggesting a potential reemergence.

Naming and etymology

editWith its vast range across the length of the Americas, Puma concolor has dozens of names and various references in the mythology of the indigenous Americans and in contemporary culture. Currently, it is referred to as "puma" by most scientists[12] and by the populations in 21 of the 23 countries in the Americas where "puma" is the common name in Spanish or Brazilian Portuguese.[13] The cat has many local or regional names in the United States and Canada, however, of which cougar, puma, mountain lion and panther are popular.[14] "Mountain lion" was a term first used in writing in 1858 from the diary of George A. Jackson of Colorado.[15] Other names include "catamount" (probably a contraction from "cat of the mountain"), "panther", "mountain screamer" and "painter". Lexicographers regard "painter" as a primarily upper-Southern US regional variant on "panther".[16] The word panther is commonly used to specifically designate the black panther, a melanistic jaguar or leopard, and the Florida panther, a subspecies of cougar (P. concolor coryi).

P. concolor holds the Guinness record for the animal with the highest number of names. It has over 40 names in English alone.[17]

"Cougar" may be borrowed from the archaic Portuguese çuçuarana; the term was originally derived from the Tupi language susua'rana, meaning "similar to deer (in hair color)". A current form in Brazil is suçuarana. It may also be borrowed from the Guaraní language term guaçu ara or guazu ara. Less common Portuguese terms are onça-parda (lit. brown onça, in distinction of the black-spotted [yellow] one, onça-pintada, the jaguar) or leão-baio (lit. chestnut lion), or unusually non-native puma or leão-da-montanha, more common names for the animal when native to a region other than South America (especially for those who do not know that suçuaranas are found elsewhere but with a different name). People in rural regions often refer to both the cougar and to the jaguar as simply gata (lit. she-cat), and outside of the Amazon, both are colloquially referred to as simply onça by many people (that is also a name for the leopard in Angola).

In the 17th century, German naturalist Georg Marcgrave named the cat the cuguacu ara. Marcgrave's rendering was reproduced by his associate, Dutch naturalist Willem Piso, in 1648. Cuguacu ara was then adopted by English naturalist John Ray in 1693.[18] The French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in 1774 (probably influenced by the word "jaguar") converted the cuguacu ara to cuguar, which was later modified to "cougar" in English.[19][20][21]

The first English record of "puma" was in 1777, where it had come from the Spanish, who in turn borrowed it from the Peruvian Quechua language in the 16th century, where it means "powerful".[22]

Taxonomy and evolution

editCougars are the largest of the small cats. They are placed in the subfamily Felinae, although their bulk characteristics are similar to those of the big cats in the subfamily Pantherinae.[2] The family Felidae is believed to have originated in Asia about 11 million years ago. Taxonomic research on felids remains partial, and much of what is known about their evolutionary history is based on mitochondrial DNA analysis,[23] as cats are poorly represented in the fossil record,[24] and there are significant confidence intervals with suggested dates. In the latest genomic study of Felidae, the common ancestor of today's Leopardus, Lynx, Puma, Prionailurus, and Felis lineages migrated across the Bering land bridge into the Americas 8.0 to 8.5 million years ago (Mya). The lineages subsequently diverged in that order.[24] North American felids then invaded South America 3 Mya as part of the Great American Interchange, following formation of the Isthmus of Panama. The cougar was originally thought to belong in Felis (Felis concolor), the genus which includes the domestic cat. As of 1993, it is now placed in Puma along with the jaguarundi, a cat just a little more than a tenth its weight.

The cougar and jaguarundi are most closely related to the modern cheetah of Africa and western Asia,[24][25] but the relationship is unresolved. The cheetah lineage is suggested by some studies to have diverged from the Puma lineage in the Americas (see American cheetah) and migrated back to Asia and Africa,[24][25] while other research suggests the cheetah diverged in the Old World itself.[26] The outline of small feline migration to the Americas is thus unclear.

A high level of genetic similarity has recently been found among North American cougar populations, suggesting they are all fairly recent descendants of a small ancestral group. Culver et al. propose the original North American population of P. concolor was extirpated during the Pleistocene extinctions some 10,000 years ago, when other large mammals, such as Smilodon, also disappeared. North America was then repopulated by a group of South American cougars.[25]

Subspecies

editUntil the late 1980s, as many as 32 subspecies were recorded; however, a recent genetic study of mitochondrial DNA[25] found many of these are too similar to be recognized as distinct at a molecular level. Following the research, the canonical Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.) recognizes six subspecies, five of which are solely found in Latin America:[2]

- Argentine cougar (Puma concolor cabrerae) Pocock, 1940:

includes the previous subspecies and synonyms hudsonii and puma - Costa Rican cougar (P. c. costaricensis) Merriam, 1901

- Eastern South American cougar (P. c. anthonyi) Nelson and Goldman, 1931:

includes the previous subspecies and synonyms acrocodia, borbensis, capricornensis, concolor, greeni, and nigra - North American cougar (P. c. couguar) Kerr, 1792:

includes the previous subspecies and synonyms arundivaga, aztecus, browni, californica, floridana, hippolestes, improcera, kaibabensis, mayensis, missoulensis, olympus, oregonensis, schorgeri, stanleyana, vancouverensis, and youngi - Northern South American cougar (P. c. concolor) Linnaeus, 1771:

includes the previous subspecies and synonyms bangsi, incarum, osgoodi, soasoaranna, sussuarana, soderstromii, suçuaçuara, and wavula - Southern South American cougar (P. c. puma) Molina, 1782:

includes the previous subspecies and synonyms araucanus, concolor, patagonica, pearsoni, and puma

- Florida panther (P. c. coryi)

The status of the Florida panther remains uncertain. It is still regularly listed as subspecies P. c. coryi in research works, including those directly concerned with its conservation.[27] Culver et al. noted low microsatellite variation in the Florida panther, possibly due to inbreeding;[25] responding to the research, one conservation team suggests, "the degree to which the scientific community has accepted the results of Culver et al. and the proposed change in taxonomy is not resolved at this time."[28]

Biology and behavior

editPhysical characteristics

editCougars are slender and agile members of the cat family. They are the fourth-largest cat;[29] adults stand about 60 to 90 cm (24 to 35 in) tall at the shoulders.[30] Adult males are around 2.4 m (7.9 ft) long nose-to-tail and females average 2.05 m (6.7 ft), with overall ranges between 1.5 to 2.75 m (4.9 to 9.0 ft) nose to tail suggested for the species in general.[31][32] Of this length, 63 to 95 cm (25 to 37 in) is comprised by the tail.[33] Males typically weigh 53 to 100 kg (115 to 220 lb), averaging 62 kg (137 lb). Females typically weigh between 29 and 64 kg (64 and 141 lb), averaging 42 kg (93 lb).[33][34][35] Cougar size is smallest close to the equator, and larger towards the poles.[3] The largest recorded cougar, shot in 1901, weighed 105.2 kg (232 lb), claims of 125.2 kg (276 lb) and 118 kg (260 lb) have been reported, though they were most likely exaggerated.[36] On average, adult male cougars in British Columbia weigh 56.7 kg (125 lb) and adult females 45.4 kg (100 lb), though several male cougars in British Columbia weighed between 86.4 and 95.5 kg (190 to 210 lb).[37]

The head of the cat is round and the ears are erect. Its powerful forequarters, neck, and jaw serve to grasp and hold large prey. It has five retractable claws on its forepaws (one a dewclaw) and four on its hind paws. The larger front feet and claws are adaptations to clutching prey.[38]

Cougars can be almost as large as jaguars, but are less muscular and not as powerfully built; where their ranges overlap, the cougar tends to be smaller on average. Besides the jaguar, the cougar is on average larger than all felids apart from lions and tigers. Despite its size, it is not typically classified among the "big cats", as it cannot roar, lacking the specialized larynx and hyoid apparatus of Panthera.[39] Compared to "big cats", cougars are often silent with minimal communication through vocalizations outside of the mother-offspring relationship.[40] Cougars sometimes voice low-pitched hisses, growls, and purrs, as well as chirps and whistles, many of which are comparable to those of domestic cats. They are well known for their screams, as referenced in some of their common names, although these screams are often misinterpreted to be the calls of other animals.[41]

Cougar coloring is plain (hence the Latin concolor) but can vary greatly between individuals and even between siblings. The coat is typically tawny, but ranges to silvery-grey or reddish, with lighter patches on the underbody, including the jaws, chin, and throat. Infants are spotted and born with blue eyes and rings on their tails;[34] juveniles are pale, and dark spots remain on their flanks.[32] Despite anecdotes to the contrary, all-black coloring (melanism) has never been documented in cougars.[42] The term "black panther" is used colloquially to refer to melanistic individuals of other species, particularly jaguars and leopards.[43]

Cougars have large paws and proportionally the largest hind legs in the cat family.[34] This physique allows it great leaping and short-sprint ability. The cougar is able to leap as high as 5.5 m (18 ft) in one bound, and as far as 40 to 45 ft (12 to 13.5 m) horizontally.[44][45][46][47] The cougar's top running speed ranges between 64 and 80 km/h (40 and 50 mph),[48][49] but is best adapted for short, powerful sprints rather than long chases. It is adept at climbing, which allows it to evade canine competitors. Although it is not strongly associated with water, it can swim.[50]

Hunting and diet

editA successful generalist predator, the cougar will eat any animal it can catch, from insects to large ungulates (over 500 kg). Like all cats, it is an obligate carnivore, meaning it needs to feed exclusively on meat to survive. The mean weight of vertebrate prey (MWVP) was positively correlated (r=0.875) with puma body weight and inversely correlated (r=–0.836) with food niche breadth all across the Americas. In general, MWVP was lower in areas closer to the Equator.[3] Its most important prey species are various deer species, particularly in North America; mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk and even bull moose are taken. Other species such as bighorn sheep, wild horses of Arizona, fallow deer, caribou, mountain goat, coyote, dall's sheep, pronghorn, domestic horses, and domestic livestock such as cattle and sheep are also primary food bases in many areas.[51] A survey of North America research found 68% of prey items were ungulates, especially deer. Only the Florida Panther showed variation, often preferring feral hogs and armadillos.[3]

Investigation in Yellowstone National Park showed that elk, followed by mule deer, were the cougar's primary targets; the prey base is shared with the park's gray wolves, with whom the cougar competes for resources.[52] Another study on winter kills (November–April) in Alberta showed that ungulates accounted for greater than 99% of the cougar diet. Learned, individual prey recognition was observed, as some cougars rarely killed bighorn sheep, while others relied heavily on the species.[53]

In Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, scat samples showed raccoons to make up 28% of the cougar's diet, harbor seals and blacktail deer 24% each, North American river otters 10%, California sea lion 7%, and American mink 4%; the remaining 3% were unidentified.[54]

In the Central and South American cougar range, the ratio of deer in the diet declines. Small to mid-size mammals are preferred, including large rodents such as the capybara. Ungulates accounted for only 35% of prey items in one survey, approximately half that of North America. Competition with the larger jaguar has been suggested for the decline in the size of prey items.[3] Other listed prey species of the cougar include mice, porcupines, beavers, raccoons, hares, guanaco, peccary, vicuna, rhea, wild turkey.[55] Birds and small reptiles are sometimes preyed upon in the south, but this is rarely recorded in North America.[3] Not all of their prey is listed here due to their large range.

Though capable of sprinting, the cougar is typically an ambush predator. It stalks through brush and trees, across ledges, or other covered spots, before delivering a powerful leap onto the back of its prey and a suffocating neck bite. The cougar is capable of breaking the neck of some of its smaller prey with a strong bite and momentum bearing the animal to the ground.[38]

Kills are generally estimated at around one large ungulate every two weeks. The period shrinks for females raising young, and may be as short as one kill every three days when cubs are nearly mature at around 15 months.[34] The cat drags a kill to a preferred spot, covers it with brush, and returns to feed over a period of days. It is generally reported that the cougar is not a scavenger, and will rarely consume prey it has not killed; but deer carcasses left exposed for study were scavenged by cougars in California, suggesting more opportunistic behavior.[56]

Reproduction and life cycle

editFemales reach sexual maturity between one-and-a-half to three years of age. They typically average one litter every two to three years throughout their reproductive lives,[57] though the period can be as short as one year.[34] Females are in estrus for about 8 days of a 23-day cycle; the gestation period is approximately 91 days.[34] Females are sometimes reported as monogamous,[58] but this is uncertain and polygyny may be more common.[59] Copulation is brief but frequent. Chronic stress can result in low reproductive rates when in captivity as well as in the field.[60]

Only females are involved in parenting. Female cougars are fiercely protective of their cubs, and have been seen to successfully fight off animals as large as American black bears in their defense. Litter size is between one and six cubs; typically two. Caves and other alcoves that offer protection are used as litter dens. Born blind, cubs are completely dependent on their mother at first, and begin to be weaned at around three months of age. As they grow, they begin to go out on forays with their mother, first visiting kill sites, and after six months beginning to hunt small prey on their own.[57] Kitten survival rates are just over one per litter.[34] When cougars are born, they have spots, but they lose them as they grow, and by the age of 2 1/2 years, they will completely be gone[61]

Young adults leave their mother to attempt to establish their own territory at around two years of age and sometimes earlier; males tend to leave sooner. One study has shown high mortality amongst cougars that travel farthest from the maternal range, often due to conflicts with other cougars (intraspecific competition).[57] Research in New Mexico has shown that "males dispersed significantly farther than females, were more likely to traverse large expanses of non-cougar habitat, and were probably most responsible for nuclear gene flow between habitat patches."[62]

Life expectancy in the wild is reported at eight to 13 years, and probably averages eight to 10; a female of at least 18 years was reported killed by hunters on Vancouver Island.[34] Cougars may live as long as 20 years in captivity. One male North American cougar (P. c. couguar), named Scratch, was two months short of his 30th birthday when he died in 2007.[63] Causes of death in the wild include disability and disease, competition with other cougars, starvation, accidents, and, where allowed, human hunting. Feline immunodeficiency virus, an endemic HIV-like virus in cats, is well-adapted to the cougar.[64]

Social structure and home range

editLike almost all cats, the cougar is a solitary animal. Only mothers and kittens live in groups, with adults meeting only to mate. It is secretive and crepuscular, being most active around dawn and dusk.

Estimates of territory sizes vary greatly. Canadian Geographic reports large male territories of 150 to 1000 km2 (58 to 386 sq mi) with female ranges half the size.[58] Other research suggests a much smaller lower limit of 25 km2 (10 sq mi), but an even greater upper limit of 1300 km2 (500 sq mi) for males.[57] In the United States, very large ranges have been reported in Texas and the Black Hills of the northern Great Plains, in excess of 775 km2 (300 sq mi).[65] Male ranges may include or overlap with those of females but, at least where studied, not with those of other males, which serves to reduce conflict between cougars. Ranges of females may overlap slightly with each other. Scrape marks, urine, and feces are used to mark territory and attract mates. Males may scrape together a small pile of leaves and grasses and then urinate on it as a way of marking territory.[50]

Home range sizes and overall cougar abundance depend on terrain, vegetation, and prey abundance.[57] One female adjacent to the San Andres Mountains, for instance, was found with a large range of 215 km2 (83 sq mi), necessitated by poor prey abundance.[62] Research has shown cougar abundances from 0.5 animals to as much as 7 (in one study in South America) per 100 km2 (38 sq mi).[34]

Because males disperse farther than females and compete more directly for mates and territory, they are most likely to be involved in conflict. Where a subadult fails to leave his maternal range, for example, he may be killed by his father.[65] When males encounter each other, they hiss, spit, and may engage in violent conflict if neither backs down.[59] Hunting or relocation of the cougar may increase aggressive encounters by disrupting territories and bringing young, transient animals into conflict with established individuals.[66]

Ecology

editDistribution and habitat

editThe cougar has the largest range of any wild land animal in the Americas. Its range spans 110 degrees of latitude, from northern Yukon in Canada to the southern Andes. Its wide distribution stems from its adaptability to virtually every habitat type: it is found in all forest types, as well as in lowland and mountainous deserts. The cougar prefers regions with dense underbrush, but can live with little vegetation in open areas.[1] Its preferred habitats include precipitous canyons, escarpments, rim rocks, and dense brush.[50]

The cougar was extirpated across much of its eastern North American range (with the exception of Florida) in the two centuries after European colonization, and faced grave threats in the remainder of its territory. Currently, it ranges across most western American states, the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, and the Canadian territory of Yukon. There have been widely debated reports of possible recolonization of eastern North America.[67] DNA evidence has suggested its presence in eastern North America,[68] while a consolidated map of cougar sightings shows numerous reports, from the mid-western Great Plains through to eastern Canada.[69] The Quebec wildlife services (known locally as MRNF) also considers cougar to be present in the province as a threatened species after multiple DNA tests confirmed cougar hair in lynx mating sites.[70] The only unequivocally known eastern population is the Florida panther, which is critically endangered. There have been unconfirmed sightings in Elliotsville Plantation, Maine (north of Monson); and in New Hampshire, there have been unconfirmed sightings as early as 1997.[71] In 2009, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources confirmed a cougar sighting in Michigan's Upper Peninsula.[72] Typically, extreme-range sightings of cougars involve young males, which can travel great distances to establish ranges away from established males; all four confirmed cougar kills in Iowa since 2000 involved males.[73]

On April 14, 2008, police shot and killed a cougar on the north side of Chicago, Illinois. DNA tests were consistent with cougars from the Black Hills of South Dakota. Less than a year later, on March 5, 2009, a cougar was photographed and unsuccessfully tranquilized by state wildlife biologists in a tree near Spooner, Wisconsin, in the northwestern part of the state.[74]

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources used motion-sensitive cameras to confirm the presence of a cougar in Greene County in southern Indiana on May 7, 2010.[75]

On June 10, 2011, a cougar was observed roaming near Greenwich, Connecticut. State officials at the time said they believed it was a released pet.[76] On June 11, 2011, a cougar, believed to be the same animal, was killed by a car on the Wilbur Cross Parkway in Milford, Connecticut.[77] When wildlife officials examined the cougar's DNA, they concluded it was a wild cougar from the Black Hills of South Dakota, which had wandered at least 1,500 miles east over an indeterminate time period.[78]

In October 2012, a trail camera in Morgan County, Illinois snapped a photograph of a cougar,[79] and on November 6, 2012 a trail camera in Pike County captured a photo also believed to be of a cougar.[80]

On November 21, 2013, a cougar was shot and killed near Morrison, Illinois in rural Whiteside County by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.[81]

On December 15, 2014, a cougar, the first seen in Kentucky since late 1800s, was treed, shot, and killed in Bourbon County, Kentucky by a Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources man.[82]

South of the Rio Grande, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) lists the cat in every Central and South American country.[1] While specific state and provincial statistics are often available in North America, much less is known about the cat in its southern range.[83]

The cougar's total breeding population is estimated at less than 50,000 by the IUCN, with a declining trend.[1] US state-level statistics are often more optimistic, suggesting cougar populations have rebounded. In Oregon, a healthy population of 5,000 was reported in 2006, exceeding a target of 3,000.[84] California has actively sought to protect the cat and a similar number of cougars has been suggested, between 4,000 and 6,000.[85]

In 2012 research in Río Los Cipreses National Reserve, Chile, based in 18 motion-sensitive cameras counted a population of two males and two females, one of them with at least two cubs, in an area of 600 km2, that is 0.63 cougars every 100 km2.[86]

Ecological role

editAside from humans, no species preys upon mature cougars in the wild, although conflicts with other predators or scavengers occur. The Yellowstone National Park ecosystem provides a fruitful microcosm to study inter-predator interaction in North America. Of the three large predators, the massive grizzly bear appears dominant, often although not always able to drive both the gray wolf pack and the cougar off their kills. One study found that American black bears visited 24% of cougar kills in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, usurping 10% of carcasses. Bears gained up to 113%, and cougars lost up to 26%, of their respective daily energy requirements from these encounters.[88] Accounts of cougars and black bears killing each other in fights to the death have been documented from the 19th century.[89][90] In spite of the size and power of the cougar, there have also been accounts of both brown and black bears killing cougars, either in disputes or in self-defense.[91][92]

The gray wolf and the cougar compete more directly for prey, especially in winter. Wolves can steal kills and occasionally kill the cat. One report describes a large pack of 7 to 11 wolves killing a female cougar and her kittens.[93] Conversely, lone female or young wolves are vulnerable to predation, and have been reported ambushed and killed by cougars.[94] Various accounts of cougars killing lone wolves, including a six-year old female, have also been documented.[95][96][97] Wolves more broadly affect cougar population dynamics and distribution by dominating territory and prey opportunities, and disrupting the feline's behavior. Preliminary research in Yellowstone, for instance, has shown displacement of the cougar by wolves.[98] In nearby Sun Valley, Idaho, a recent cougar/wolf encounter that resulted in the death of the cougar was documented.[99] One researcher in Oregon noted: "When there is a pack around, cougars are not comfortable around their kills or raising kittens ... A lot of times a big cougar will kill a wolf, but the pack phenomenon changes the table."[100]

Both species, meanwhile, are capable of killing mid-sized predators, such as bobcats and coyotes, and tend to suppress their numbers.[52] Although cougars can kill coyotes, the latter have been documented attempting to prey on cougar cubs.[101]

In the southern portion of its range, the cougar and jaguar share overlapping territory.[102] The jaguar tends to take larger prey and the cougar smaller where they overlap, reducing the cougar's size and also further reducing the likelihood of direct competition.[3] Of the two felines, the cougar appears best able to exploit a broader prey niche and smaller prey.[103]

As with any predator at or near the top of its food chain, the cougar impacts the population of prey species. Predation by cougars has been linked to changes in the species mix of deer in a region. For example, a study in British Columbia observed that the population of mule deer, a favored cougar prey, was declining while the population of the less frequently preyed-upon white-tailed deer was increasing.[104] The Vancouver Island marmot, an endangered species endemic to one region of dense cougar population, has seen decreased numbers due to cougar and gray wolf predation.[105] Nevertheless, there is a measurable effect on the quality of deer populations by puma predation.[106][107]

In the southern part of South America, the puma is a top level predator that has controlled the population of guanaco and other species since prehistoric times.[108]

Hybrids

editA pumapard is a hybrid animal resulting from a union between a cougar and a leopard. Three sets of these hybrids were bred in the late 1890s and early 1900s by Carl Hagenbeck at his animal park in Hamburg, Germany. Most did not reach adulthood. One of these was purchased in 1898 by Berlin Zoo. A similar hybrid in Berlin Zoo purchased from Hagenbeck was a cross between a male leopard and a female puma. Hamburg Zoo's specimen was the reverse pairing, the one in the black-and-white photo, fathered by a puma bred to an Indian leopardess.

Whether born to a female puma mated to a male leopard, or to a male puma mated to a female leopard, pumapards inherit a form of dwarfism. Those reported grew to only half the size of the parents. They have a puma-like long body (proportional to the limbs, but nevertheless shorter than either parent), but short legs. The coat is variously described as sandy, tawny or greyish with brown, chestnut or "faded" rosettes.[109]

Conservation status

editThe World Conservation Union (IUCN) currently lists the cougar as a "least concern" species. The cougar is regulated under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES),[110] rendering illegal international trade in specimens or parts.

In the United States east of the Mississippi River, the only unequivocally known cougar population is the Florida panther. Until 2011, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) recognized both an Eastern cougar (claimed to be a subspecies by some, denied by others)[111][112] and the Florida panther, affording protection under the Endangered Species Act.[113][114] Certain taxonomic authorities have collapsed both designations into the North American cougar, with Eastern or Florida subspecies not recognized,[2] while a subspecies designation remains recognized by some conservation scientists.[27] The most recent documented count for the Florida sub-population is 87 individuals, reported by recovery agencies in 2003.[115] In March 2011, the USFWS declared the Eastern cougar extinct. However, with the taxonomic uncertainty about its existence as a subspecies as well as the possibility of eastward migration of cougars from the western range, the subject remains open.[116]

This uncertainty has been recognized by Canadian authorities. The Canadian federal agency called Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada rates its current data as "insufficient" to draw conclusions regarding the eastern cougar's survival, and says on its Web site "Despite many sightings in the past two decades from eastern Canada, there are insufficient data to evaluate the taxonomy or assign a status to this cougar." Notwithstanding numerous reported sightings in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, it has been said that the evidence is inconclusive: ". . . there may not be a distinct 'eastern' subspecies, and some sightings may be of escaped pets."[117][118]

The cougar is also protected across much of the rest of its range. As of 1996, cougar hunting was prohibited in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, French Guiana, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, and Uruguay. The cat had no reported legal protection in Ecuador, El Salvador, and Guyana.[34] Regulated cougar hunting is still common in the United States and Canada, although they are protected from all hunting in the Yukon; it is permitted in every U.S. state from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, with the exception of California. Texas is the only state in the United States with a viable population of cougars that does not protect that population in some way. In Texas, cougars are listed as nuisance wildlife and any person holding a hunting or a trapping permit can kill a cougar regardless of the season, number killed, sex or age of the animal.[119] Killed animals are not required to be reported to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Conservation work in Texas is the effort of a non-profit organization, Balanced Ecology Inc (BEI), as part of their Texas Mountain Lion Conservation Project.[120] Cougars are generally hunted with packs of dogs, until the animal is 'treed'. When the hunter arrives on the scene, he shoots the cat from the tree at close range. The cougar cannot be legally killed without a permit in California except under very specific circumstances, such as when a cougar is in act of pursuing livestock or domestic animals, or is declared a threat to public safety.[85] Permits are issued when owners can prove property damage on their livestock or pets. For example, multiple dogs have been attacked and killed, sometimes while with the owner. Many attribute this to the protection cougars have from being hunted and are now becoming desensitized to humans; most are removed from the population after the attacks have already occurred. Statistics from the Department of Fish and Game indicate that cougar killings in California have been on the rise since the 1970s with an average of over 112 cats killed per year from 2000 to 2006 compared to six per year in the 1970s. They also state on their website that there is a healthy number of cougars in California. The Bay Area Puma Project aims to obtain information on cougar populations in the San Francisco Bay area and the animals' interactions with habitat, prey, humans, and residential communities.[121]

Conservation threats to the species include persecution as a pest animal, environmental degradation and habitat fragmentation, and depletion of their prey base. Wildlife corridors and sufficient range areas are critical to the sustainability of cougar populations. Research simulations have shown that the animal faces a low extinction risk in areas of 2200 km2 (850 sq mi) or more. As few as one to four new animals entering a population per decade markedly increases persistence, foregrounding the importance of habitat corridors.[122]

On March 2, 2011, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared the Eastern cougar (Puma concolor couguar) officially extinct.[123]

Relationships with humans

editIn mythology

editThe grace and power of the cougar have been widely admired in the cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Inca city of Cusco is reported to have been designed in the shape of a cougar, and the animal also gave its name to both Inca regions and people. The Moche people represented the puma often in their ceramics.[124] The sky and thunder god of the Inca, Viracocha, has been associated with the animal.[125]

In North America, mythological descriptions of the cougar have appeared in the stories of the Hocąk language ("Ho-Chunk" or "Winnebago") of Wisconsin and Illinois[126] and the Cheyenne, amongst others. To the Apache and Walapai of Arizona, the wail of the cougar was a harbinger of death.[127] The Algonquins and Ojibwe believe that the cougar lived in the underworld and was wicked, whereas it was a sacred animal among the Cherokee.[128]

Livestock predation

editDuring the early years of ranching, cougars were considered on par with wolves in destructiveness. According to figures in Texas in 1990, 86 calves (0.0006% of a total of 13.4 million cattle & calves in Texas), 253 Mohair goats, 302 Mohair kids, 445 sheep (0.02% of a total of 2.0 million sheep & lambs in Texas) and 562 lambs (0.04% of 1.2 million lambs in Texas) were confirmed to have been killed by cougars that year.[129][130] In Nevada in 1992, cougars were confirmed to have killed 9 calves, 1 horse, 4 foals, 5 goats, 318 sheep and 400 lambs. In both cases, sheep were the most frequently attacked. Some instances of surplus killing have resulted in the deaths of 20 sheep in one attack.[131] A cougar's killing bite is applied to the back of the neck, head, or throat and they inflict puncture marks with their claws usually seen on the sides and underside of the prey, sometimes also shredding the prey as they hold on. Coyotes also typically bite the throat region but do not inflict the claw marks and farmers will normally see the signature zig-zag pattern that coyotes create as they feed on the prey whereas cougars typically drag in a straight line. The work of a cougar is generally clean, differing greatly from the indiscriminate mutilation by coyotes and feral dogs. The size of the tooth puncture marks also helps distinguish kills made by cougars from those made by smaller predators.[132]

Remedial hunting appears to have the paradoxical effect of increased livestock predation and complaints of human-puma conflicts. In a 2013 study the most important predictor of puma problems were remedial hunting of puma the previous year. Each additional puma on the landscape increased predation and human-puma complaints by 5% but each additional animal killed on the landscape the previous year increased complaints by 50%, an order of magnitude higher. The effect had a dose-response relationship with very heavy (100% removal of adult puma) remedial hunting leading to a 150% – 340% increase in livestock and human conflicts.[133] This effect is attributed to the fact that inexperienced younger male pumas are most likely to approach human developments, whereas remedial hunting removes older pumas who have learned to avoid people in their established territories. Remedial hunting enables younger males to enter the former territories of the older animals.[134][135]

Attacks on humans

editDue to the expanding human population, cougar ranges increasingly overlap with areas inhabited by humans. Attacks on humans are very rare, as cougar prey recognition is a learned behavior and they do not generally recognize humans as prey.[11] Attacks on people, livestock, and pets may occur when a puma habituates to humans or is in a condition of severe starvation. Attacks are most frequent during late spring and summer, when juvenile cougars leave their mothers and search for new territory.[87]

Between 1890 and 1990, in North America there were 53 reported, confirmed attacks on humans, resulting in 48 nonfatal injuries and 10 deaths of humans (the total is greater than 53 because some attacks had more than one victim).[136] By 2004, the count had climbed to 88 attacks and 20 deaths.[137]

Within North America, the distribution of attacks is not uniform. The heavily populated state of California has seen a dozen attacks since 1986 (after just three from 1890 to 1985), including three fatalities.[85] Lightly populated New Mexico reported an attack in 2008, the first there since 1974.[138]

As with many predators, a cougar may attack if cornered, if a fleeing human stimulates their instinct to chase, or if a person "plays dead". Standing still however may cause the cougar to consider a person easy prey.[139] Exaggerating the threat to the animal through intense eye contact, loud shouting, and any other action to appear larger and more menacing, may make the animal retreat. Fighting back with sticks and rocks, or even bare hands, is often effective in persuading an attacking cougar to disengage.[11][87]

When cougars do attack, they usually employ their characteristic neck bite, attempting to position their teeth between the vertebrae and into the spinal cord. Neck, head, and spinal injuries are common and sometimes fatal.[11] Children are at greatest risk of attack, and least likely to survive an encounter. Detailed research into attacks prior to 1991 showed that 64% of all victims – and almost all fatalities – were children. The same study showed the highest proportion of attacks to have occurred in British Columbia, particularly on Vancouver Island where cougar populations are especially dense.[136] Preceding attacks on humans, cougars display aberrant behavior, such as activity during daylight hours, a lack of fear of humans, and stalking humans. There have sometimes been incidents of pet cougars mauling people.[140][141]

Research on new wildlife collars may be able to reduce human-animal conflicts by predicting when and where predatory animals hunt. This can not only save human lives and the lives of their pets and livestock but also save these large predatory mammals that are important to the balance of ecosystems.[142]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Template:IUCN2014.3

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Template:MSW3 Wozencraft

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Iriarte, J. Agustin; Franklin, William L.; Johnson, Warren E.; Redford, Kent H. (1990). "Biogeographic variation of food habits and body size of the America puma". Oecologia. 85 (2): 185. doi:10.1007/BF00319400.

- ^ Cougars. US National Park Service.

- ^ Hansen, Kevin. (1992) Cougar: The American Lion. Northland. Flagstaff, AZ, ch. 4, ISBN 0873585445.

- ^ Cougar Education & Identification Course. New Mexico Department of Game & Fish

- ^ Living With California Mountain Lions. California Department of Game & Fish

- ^ Hartwell, Sarah. The Domestication of the Cat. messybeast.com

- ^ Small Wild Cat Species. messybeast.com

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 544–46. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McKee, Denise (2003). "Cougar Attacks on Humans: A Case Report". Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. 14 (3). Wilderness Medical Society: 169–73. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2003)14[169:CAOHAC]2.0.CO;2. PMID 14518628.

- ^ "Mountain Lion (Puma, Cougar)". San Diego Zoo. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ "Puma concolor". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ doi:10.3923/javaa.2010.601.603

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ Jackson, George A. (1935). LeHafen, Roy (ed.). George A. Jackson's Diary of 1858–1859. Vol. 6. pp. 201–214.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "painter". transcription of the American Heritage Dictionary, Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2001. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ The Guinness Book of World Records. 2004. p. 49.

- ^ "Words to the Wise". Take Our Word for it (205): 2. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "jaguar". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "cougar". Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online.

- ^ "cougar". Oxford Dictionaries Online, Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ "The Puma". Projeto Puma. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (January 6, 2006). "DNA Offers New Insight Concerning Cat Evolution". New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S.J. (January 6, 2006). "The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Culver, M.; Johnson, W.E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; O'Brien, S.J. (2000). "Genomic Ancestry of the American Puma". Journal of Heredity. 91 (3): 186–97. doi:10.1093/jhered/91.3.186. PMID 10833043.

- ^ Barnett, Ross; Barnes, Ian; Phillips, Matthew J.; Martin, Larry D.; Harington, C. Richard; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Cooper, Alan (2005). "Evolution of the extinct Sabretooths and the American cheetah-like cat". Current Biology. 15 (15): R589–R590. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.052. PMID 16085477.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conroy, Michael J.; Beier, Paul; Quigley, Howard; Vaughan, Michael R. (2006). "Improving The Use Of Science In Conservation: Lessons From The Florida Panther". Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1:ITUOSI]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ The Florida Panther Recovery Team (January 31, 2006). "Florida Panther Recovery Program (Draft)" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ^ Expanding Cougar Population The Cougar Net.org

- ^ Florida Panther Facts. Florida Panther Refuge

- ^ "Mountain Lion (Puma concolor)". Texas Parks and Wildlife. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Eastern Cougar Fact Sheet". New York State Department of Environmental Conservat ion. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shivaraju, A. (2003) Puma concolor. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on September 15, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Nowell, K. and Jackson, P (2006). "Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan" (PDF). IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Puma concolor – Mountain Lion – Discover Life". Pick4.pick.uga.edu. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Hornocker, Maurice (2010). Cougar : ecology and conservation. Chicago [etc.] : University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226353443.

- ^ Spalding, D. J. "Cougar in British Columbia". British Columbia Fish and Wildlife Branch.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Cougar". Hinterland Who's Who. Canadian Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ Weissengruber, GE; Forstenpointner G; Peters G; Kübber-Heiss A; Fitch WT (2002). "Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and domestic cat (Felis silvestris f. catus)". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (3). Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 195–209. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00088.x. PMC 1570911. PMID 12363272.

- ^ Hornocker, Maurice G. and Negri, Sharon (December 15, 2009). Cougar: ecology and conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-0-226-35344-9. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "About Eastern Cougars". Eastern Cougar Foundation. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ "Black cougar more talk than fact". Tahlequah Daily Press. February 1, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

Game Warden: Never in the history of the United States has there ever been, in captivity or in the wild, a documented black mountain lion

- ^ "Mutant Pumas". messybeast.com.

- ^ "Mountain Lion (Puma, Cougar)". San Diego Zoo.org. Zoological Society of San Diego. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ Cougar: Puma concolor: A Saskatchewan Species at Risk. Saskatoon Zoo Society, Canada.

- ^ Cougar. bluelion.org.

- ^ Hansen, Kevin (1990). "Ch. 4 – An Almost Perfect Predator". Cougar: The American Lion. Mountain Lion Foundation.

- ^ "Cougar". Zoological Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ Mountain Lion FAQ and Facts. Mountainlion.org. Retrieved on April 29, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mountain Lion, Felis concolor". Sierra Club. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Turner, John W.; Morrison, Michael L. (2008). "Influence of Predation by Mountain Lions on Numbers and Survivorship of a Feral Horse Population". The Southwestern Naturalist. 46 (2): 183–190. doi:10.2307/3672527. JSTOR 3672527.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Wildlife: Wolves". Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

* Akenson, Holly; Akenson, James and Quigley, Howard. "Winter Predation and Interactions of Wolves and Cougars on Panther Creek in Central Idaho".{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

* Oakleaf, John K.; Mack, Curt and Murray, Dennis L. "Winter Predation and Interactions of Cougars and Wolves in the Central Idaho Wilderness".{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ross, R.; Jalkotzy, M. G.; Festa-Bianchet, M. (1993). "Cougar predation on bighorn sheep in southwestern Alberta during winter". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 75 (5): 771–75. doi:10.1139/z97-098.

- ^ "British Columbia cougars found to prey on seals, sea lions". February 23, 2012. Retrieved March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Whitaker, John O. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals. Chanticleer Press, New York, 1980, pg. 598. ISBN 0-394-50762-2.

- ^ Bauer, Jim W.; Logan, Kenneth A.; Sweanor, Linda L.; Boyce, Walter M. (December 2005). Jones, Cheri A. (ed.). "Scavenging behavior in Puma". The Southwestern Naturalist. 50 (4): 466–471. doi:10.1894/0038-4909(2005)050[0466:SBIP]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Cougar Discussion Group (January 27, 1999). "Utah Cougar Management Plan (Draft)" (PDF). Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Cougars in Canada (Just the Facts)". Canadian Geographic Magazine. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hamilton, Matthew; Hundt, Peter and Piorkowski, Ryan. "Mountain Lions". University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bonier, F.; Quigley, H.; Austad, S. (2004). "A technique for non-invasively detecting stress response in cougars" (PDF). Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32 (3): 711–717. doi:10.2193/0091-7648(2004)032[0711:ATFNDS]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ "Staying safe in cougar country". Wildlife.utah.gov. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sweanor, Linda; Logan, Kenneth A.; Hornocker, Maurice G. (2000). "Cougar Dispersal Patterns, Metapopulation Dynamics, and Conservation". Conservation Biology. 14 (3): 798–808. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99079.x.

- ^ "Scratch". bigcatrescue.org. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ Biek, Roman; Rodrigo, Allen G.; Holley, David; Drummond, Alexei; Anderson Jr., Charles R.; Ross, Howard A.; Poss, Mary (2003). "Epidemiology, Genetic Diversity, and Evolution of Endemic Feline Immunodeficiency Virus in a Population of Wild Cougars". Journal of Virology. 77 (17): 9578–89. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.17.9578-9589.2003. PMC 187433. PMID 12915571.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mahaffy, James (December 2004). "Behavior of cougar in Iowa and the Midwest". Dordt College. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ "Mountain Lion (Felis concolor) study on Boulder Open Space" (PDF). Letter to the Parks and Open Space Advisory Committee, Boulder, Colorado. Sinapu. March 22, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ Marschall, Laurence A. (March 2005). "Bookshelf". Natural Selections. Natural History Magazine. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ^ Belanger, Joe (May 25, 2007). "DNA tests reveal cougars roam region". London Free Press. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ Board of Directors (2004). "The "Big" Picture". The Cougar Network. Retrieved May 20, 2007. The Cougar Network methodology is recognized by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ "Your part in helping endangered species". Ministry of Wildlife and Natural Resources, Quebec, Canada. 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Davidson, Rick (2009). "NH Sightings Catamount" (PDF). Beech River Books. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ Skinner, Victor (November 15, 2009). "Photo shows cougar presence in Michigan". The Grand Rapids Press. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Cedar Rapids man shoots mountain lion in Iowa County". Cedar Rapids Gazette. December 15, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Carlson, James A. (April 22, 2009). "Sightings show cougars expanding into central US". Seattle Times. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Mountain Lion Confirmed in Rural Greene County". Indiana Department of Natural Resources. May 7, 2010.

- ^ "Mountain lion reportedly spotted roaming Connecticut town". Fox News. June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "Mountain Lion killed by car on Connnecticut highway". CNN. June 11, 2011.

- ^ Baron, David (July 29, 2011) The Cougar Behind Your Trash Can. New York Times.

- ^ "Cougar photographed in Morgan County". The State Journal-Register. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ "Jury's still out, but Pike County cougar sighting could be state's third in two months". The State Journal-Register. November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ "Timeline Photos". Facebook. November 21, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "First cougar seen in Kentucky since Civil War is killed". December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Cougar facts" (PDF). National Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "Cougar Management Plan". Wildlife Division: Wildlife Management Plans. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mountain Lions in California". California Department of Fish and Game. 2004. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Research of Nicolás Guarda, supported by Conaf, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, and a private Enterprise. See article in Chilean newspaper La Tercera, Investigación midió por primera vez población de pumas en zona central, retrieved on January 28, 2013, in Spanish Language.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Safety Guide to Cougars". Environmental Stewardship Division. Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Environment. 1991. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ^ COSEWIC. Canadian Wildlife Service (2002). "Assessment and Update Status Report on the Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos)" (PDF). Environment Canada. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Turnbo, S. C. "A Fight to a Finish Between a Bear and Panther". thelibrary.org.

- ^ Turnbo, S. C. "Finding a Panther Guarding a Dead Bear". thelibrary.org.

- ^ "Cougar vs Bears Accounts". Everything about the Cougar/Mountain Lion. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Hornocker, M., and Negri, S. (Eds.). (2009). Cougar: ecology and conservation. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL, ISBN 0226353443.

- ^ "Park wolf pack kills mother cougar". forwolves.org. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ Gugliotta, Guy (May 19, 2003). "In Yellowstone, it's Carnivore Competition". Washington Post. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ "Wolf B4 Killed by Mountain Lion?". forwolves.org. March 25, 1996.

- ^ "Autopsy Indicates Cougar Killed Wolf". igorilla.com. Retrieved April 2000.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Mountain lions kill collared wolves in Bitteroot". missoulian.com. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "Overview: Gray Wolves". Greater Yellowstone Learning Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ "Predators clash above Elkhorn". Idaho Mountain Express. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Cockle, Richard (October 29, 2006). "Turf wars in Idaho's wilderness". The Oregonian. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ "Cougars vs. coyotes photos draw Internet crowd". missoulian.com. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ Hamdig, Paul. "Sympatric Jaguar and Puma". Ecology Online Sweden. Archived from the original on July 16, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ Nuanaez, Rodrigo; Miller, Brian; Lindzey, Fred (2000). "Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico". Journal of Zoology. 252 (3): 373. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00632.x.

- ^ Robinson, Hugh S.; Wielgus, Robert B.; Gwilliam, John C. (2002). "Cougar predation and population growth of sympatric mule deer and white-tailed deer". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 80 (3): 556–68. doi:10.1139/z02-025.

- ^ Bryant, Andrew A.; Page, Rick E. (May 2005). "Timing and causes of mortality in the endangered Vancouver Island marmot (Marmota vancouverensis)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 83 (5): 674–82. doi:10.1139/z05-055.

- ^ Fountain, Henry (November 16, 2009) "Observatory: When Mountain Lions Hunt, They Prey on the Weak". New York Times.

- ^ Weaver, John L.; Paquet, Paul C.; Ruggiero, Leonard F. (1996). "Resilience and Conservation of Large Carnivores in the Rocky Mountains". Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 964. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10040964.x.

- ^ Busch, Robert H. The Cougar Almanac. New York, 2000, pg 94. ISBN 1592282954.

- ^ "Geocites – Liger & Tigon Info". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "Appendices I, II and III". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ^ Bolgiano, Chris (August 1995). Mountain Lion:An Unnatural History of Pumas and People (Hardcover ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1044-2.

- ^ Eberhart, George M. (2002). Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology. Vol. Volume 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 153–161. ISBN 1-57607-283-5.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Eastern Cougar". Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "Florida Panther". Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Archived from the original on June 4, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ "Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2002–2003 Panther Genetfic Restoration Annual Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (March 2, 2011). "U.S. Declares Eastern Cougar Extinct, With an Asterisk". The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Committee on Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Cosewic.gc.ca. Retrieved on September 15, 2011.

- ^ Eastern Cougar, Nature Canada. Naturecanada.ca. Retrieved on September 15, 2011.

- ^ TPWD: Mountain Lions. Tpwd.state.tx.us (July 16, 2007). Retrieved on September 15, 2011.

- ^ Texas Mountain Lion Conservation Project. Balanced Ecology Inc. balancedecology.org

- ^ "Bay Area Puma Project (BAPP)". Felidae Conservation Fund. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Beier, Paul (March 1993). "Determining Minimum Habitat Areas and Habitat Corridors for Cougars". Conservation Biology. 7 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07010094.x. JSTOR 2386646.

- ^ Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Fws.gov. Retrieved on September 15, 2011.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Tarmo, Kulmar. "On the role of Creation and Origin Myths in the Development of Inca State and Religion". Electronic Journal of Folklore. Kait Realo (translator). Estonian Folklore Institute. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ Cougars, The Encyclopedia of Hočąk (Winnebago) Mythology. Retrieved: 2009/12/08.

- ^ "Living with Wildlife: Cougars" (PDF). USDA Wildlife Services. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Matthews, John and Matthews, Caitlín (2005). The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. HarperElement. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-4351-1086-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cattle report 1990" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ "Sheep and Goats report 1990" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ "Mountain Lion Fact Sheet". Abundant Wildlife Society of North America. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- ^ "Cougar Predation – Description". Procedures for Evaluating Predation on Livestock and Wildlife. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Peebles, Kaylie A.; Wielgus, Robert B.; Maletzke, Benjamin T.; Swanson, Mark E. (November 2013). "Effects of Remedial Sport Hunting on Cougar Complaints and Livestock Depredations". PLOS One. 8 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Beier, Paul (1991). "Cougar attacks on humans in the United States and Canada". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 19: 403–412. JSTOR 3782149.

- ^ Torres SG; Mansfield TM; Foley JE; Lupo T; Brinkhaus A (1996). "Mountain lion and human activity in California: testing speculations". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 24 (3): 451–460. JSTOR 3783326.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beier, Paul (1991). "Cougar attacks on humans in United States and Canada". Wildlife Society Bulletin. Northern Arizon University. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "Confirmed mountain lion attacks in the United States and Canada 1890 – present". Arizona Game and Fish Department. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ New Mexico Department of Game and Fish: Search continues for mountain lion that killed Pinos Altos man, June 23, 2008; Wounded mountain lion captured, killed near Pinos Altos, June 25, 2008; Second mountain lion captured near Pinos Altos, July 1, 2008

- ^ Subramanian, Sushma (April 14, 2009). "Should You Run or Freeze When You See a Mountain Lion?". Scientific American. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ "Neighbor saves Miami teen from cougar". MSNBC. Associated Press. November 16, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ "2-Year-Old Boy Hurt In Pet Cougar Attack". New York Times. June 4, 1995.

- ^ Williams, Terrie M. (November 6, 2014) "As species decline, so does research funding" Los Angeles Times

Further reading

edit- Baron, David (2004). The Beast in the Garden: A Modern Parable of Man and Nature. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-05807-7.

- Bolgiano, Chris (2001). Mountain Lion:An Unnatural History of Pumas and People (Paperback ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2867-6.

- Eberhart, George M. (2002). Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology. Vol. Volume 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 153–161. ISBN 1-57607-283-5.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hamm, Neil (November 2007). "Survival Stories: Mauled by a Cougar". Outside magazine. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- Hornocker, Maurice; Negri, Sharon; Lindzey, Fred, eds. (2010). Cougar: Ecology and Conservation (Hardcover ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35344-9.

- Kobalenko, Jerry (2005). Forest Cats of North America. Hove: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 1-55209-172-4.

- Lester, Todd (October 2001). "Search for Cougars in the East North America" (PDF). North American BioFortean Review. 3 (7). Zoological Miscellania website: 15–17.

- Logan, Ken; Linda Sweanor (2001). Desert Puma: Evolutionary Ecology and Conservation of an Enduring Carnivore. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-866-4.

- "Publications". Mountain Lion Foundation.

- Parker, Gerry (1994). The Eastern Panther – Mystery Cat of the Appalachians (Softcover ed.). Nimbus Publishing (CN). ISBN 1-55109-268-9.

- Wright, Bruce S (1972). The Eastern Panther: A Question of Survival. Toronto: Clark, Irwin, and Company. ISBN 0772005281.

- "Annotated Bibliography". easterncougar.org – Cougar Rewilding Foundation.

External links

edit

- Species portrait Puma concolor; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Cougar Tracks: How to identify cougar tracks in the wild

- Puma sounds (they growl, hiss and scream but cannot roar like true lions of the genus Panthera) at National Geographic Society

- Santa Cruz Puma Project

- Eastern Puma Research Network

- Felidae Conservation Fund

- Cougar Rewilding Foundation, formerly "Eastern Cougar Foundation"

- The Cougar Network --Using Science to Understand Cougar Ecology

- Mountain Lion Foundation – Saving America's Lion

- SaveTheCougar.org: Sightings of cougars in Michigan

- People and Cougar/Jaguars A Guide for Coexistence

- The Cougar Fund – Protecting America's Greatest Cat. A Definitive Resource About Cougars] Comprehensive, non-profit 501(c)(3) site with extensive information about cougars, from how to live safely in cougar country, to science abstracts, hunting regulations, state-by-state cougar management/policy info, and rare photos and videos of wild cougars.

- Living with California Mountain Lions