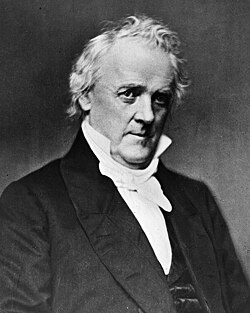

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. (/bjuːˈkænən/; April 23, 1791 – June 1, 1868) was the 15th President of the United States (1857–61), serving immediately prior to the American Civil War. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States House of Representatives and later the Senate, then served as Minister to Russia under President Andrew Jackson. He was named Secretary of State under President James K. Polk, and as of 2016[update] is the last former Secretary of State to serve as President of the United States. After Buchanan turned down an offer to sit on the Supreme Court, President Franklin Pierce appointed him Ambassador to the United Kingdom, in which capacity he helped draft the Ostend Manifesto.

| James Buchanan | |

|---|---|

| |

| 15th President of the United States | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 4, 1861 | |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge |

| Preceded by | Franklin Pierce |

| Succeeded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office August 23, 1853 – March 15, 1856 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Joseph Reed Ingersoll |

| Succeeded by | George Dallas |

| 17th United States Secretary of State | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office March 10, 1845 – March 7, 1849 | |

| President | James K. Polk Zachary Taylor |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | John M. Clayton |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office December 6, 1834 – March 5, 1845 | |

| Preceded by | William Wilkins |

| Succeeded by | Simon Cameron |

| United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office January 4, 1832 – August 5, 1833 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Randolph |

| Succeeded by | Mahlon Dickerson |

| Chairman of the House Committee on the Judiciary | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office March 5, 1829 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Pendleton Barbour |

| Succeeded by | Warren R. Davis |

| Ambassador to | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 4th district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by | James S. Mitchell |

| Succeeded by | William Hiester |

| Ambassador to | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 3rd district | |

| In office March 4, 1821 – March 3, 1823 | |

| Preceded by | Jacob Hibshman |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Miller |

| Member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office 1814-1816 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Template:MONTHNAME 23, 1791 Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 1, 1868 (aged 77) Lancaster, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodward Hill Cemetery Lancaster, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | None |

| Alma mater | Dickinson College |

| Profession | Lawyer Diplomat Politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Template:Country data United States of America |

| Service/branch | Pennsylvania Militia |

| Years of service | 1814 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | Henry Shippen's Company, 1st Brigade, 4th Division |

| Battles/wars | Defense of Baltimore |

Buchanan was nominated by the Democratic Party in the 1856 presidential election. Throughout most of Pierce's term, he had been stationed in London as minister to the Court of St. James's and so was not caught up in the crossfire of sectional politics that dominated the country. His subsequent election victory took place in a three-man race with John C. Frémont and Millard Fillmore. As President, he was often called a "doughface", a Northerner with Southern sympathies, who battled with Stephen A. Douglas for control of the Democratic Party. Buchanan's efforts to maintain peace between the North and the South alienated both sides, and the Southern states declared their secession in the prologue to the American Civil War. Buchanan's view was that secession was illegal, but that going to war to stop it was also illegal. Buchanan, an attorney, was noted for his mantra, "I acknowledge no master but the law."[1]

By the time he left office, popular opinion was against him and the Democratic Party had split. Buchanan had once aspired to be a president who would rank in history with George Washington.[2] However, his inability to identify a ground for peace or address the sharply divided pro-slavery and anti-slavery partisans with a unifying principle on the brink of the Civil War has led to his consistent ranking by historians as one of the worst presidents in American history. Historians in both 2006 and 2009 voted his failure to deal with secession the worst presidential mistake ever made.[3]

He is, to date, the only president from Pennsylvania and the only president to remain a lifelong bachelor. He was the last president born in the 18th century.

Early life

editJames Buchanan, Jr. was born in a log cabin in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania (now Buchanan's Birthplace State Park), in Franklin County, on April 23, 1791, to James Buchanan, Sr. (1761–1821), a businessman, merchant, and farmer, and Elizabeth Speer, an educated woman (1767–1833).[4] His parents were both of Ulster Scots descent, the father having emigrated from Donegal, Ireland, in 1783. Buchanan had six sisters and four brothers.[4]

In 1797, the family moved to nearby Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. The home in Mercersburg was later turned into the James Buchanan Hotel.[5]

Buchanan attended the village academy (Old Stone Academy) and later Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Though he was nearly expelled at one point for poor behavior, he pleaded for a second chance and subsequently graduated with honors on September 19, 1809.[6] Later that year, he moved to Lancaster, where he studied law with attorney James Hopkins. Buchanan was admitted to the bar in 1812, and practiced in Lancaster.[7]

A dedicated Federalist, he initially opposed the War of 1812 because he believed it was an unnecessary conflict. Despite his initial opposition to the war, when the British invaded neighboring Maryland in 1814, he enlisted as a private in Henry Shippen's Company, 1st Brigade, 4th Division, Pennsylvania Militia, a unit of light dragoons, and served in the defense of Baltimore.[8][9][10] Buchanan is the only president with military experience who did not, at some point, serve as an officer.[11]

An active Freemason, he was the Master of Masonic Lodge No. 43 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and a District Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania.[12]

Political career

editBuchanan began his political career in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives (1814–16) as a member of the Federalist Party.[13] He was elected to the 17th United States Congress and to the four succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1821 – March 3, 1831), serving as chairman of the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary in the 21st United States Congress. In 1830, he was among the members appointed by the House to conduct impeachment proceedings against James H. Peck, judge of the United States District Court for the District of Missouri. Peck was charged with abuse of the contempt power, but was ultimately acquitted.[14] Buchanan did not seek reelection, and from 1832 to 1833, he served as Minister to Russia, appointed by Andrew Jackson.

With the Federalist Party long defunct, Buchanan was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate to fill a vacancy and served from December 1834; he was reelected in 1837 and 1843, and resigned in 1845 to accept appointment as Secretary of State in the administration of President James K. Polk. He was chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations from 1836 to 1841.[15]

After the death of Supreme Court Justice Henry Baldwin in 1844, Polk nominated Buchanan to fill the vacancy in March 1845, but he declined that nomination because he felt compelled to complete his collaboration on the Oregon Treaty negotiations. The seat was eventually filled by Robert Cooper Grier.[16]

Buchanan served as Secretary of State under Polk from 1845 to 1849, despite objections from Buchanan's rival, Vice President George Dallas.[17] In this capacity, he helped negotiate the 1846 Oregon Treaty establishing the 49th parallel as the northern boundary of the western United States.[18] To date, Buchanan is the last former Secretary of State to have become President.

In 1852, Buchanan was named president of the Board of Trustees of Franklin and Marshall College in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and he served in this capacity until 1866,[19] despite a false report that he was fired.[20]

He served as minister to the Court of St. James's (Britain) from 1853 to 1856, during which time he helped to draft a memorandum that became known as the Ostend Manifesto. He signed the memorandum along with Pierre Soulé and John Mason. This document proposed the purchase from Spain of Cuba, then in the midst of revolution and near bankruptcy, declaring the island "as necessary to the North American republic as any of its present ... family of states." Against Buchanan's recommendation, the final draft of the manifesto suggested that "wresting it from Spain" if Spain refused to sell would be justified "by every law, human and Divine".[21] The manifesto, generally considered a blunder overall, was never acted upon, but weakened the Pierce administration and support for Manifest Destiny.[21][22]

Presidential election of 1856

editIn 1856, Democrats selected Buchanan as their nominee for President of the United States. He had been in England during the Kansas-Nebraska debate and thus remained untainted by either side.[23] Pennsylvania, which had three times failed Buchanan, now gave him full support in its state convention. Though he never declared his candidacy, it is apparent from all his correspondence that he was aware of the distinct possibility of his nomination by the Democratic convention in Cincinnati, even before heading home at the finish of his work as Minister to the Court of St. James in the United Kingdom. Writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, then serving as American Consul in Liverpool, recorded in his diary that Buchanan visited him in January 1855:

He returns to America, he says, next October, and then retires forever from public life... as regards his prospects for the Presidency, [h]e said that his mind was fully made up, and that he would never be a candidate, and that he had expressed this decision to his friends in such a way as to put it out of his own power to change it... that it was now too late, and that he was too old... although, really, he is the only Democrat, at this moment, whom it would not be absurd to talk of for the office.... I wonder whether he can have had any object in saying all this to me. He might see that it would be perfectly natural for me to tell it to General Pierce.[24]

Jonathan Foltz told Buchanan in November 1855, "The people have taken the next presidency out of the hands of the politicians...the people and not your political friends will place you there." While Buchanan did not overtly seek the office, he most deliberately chose not to discourage the movement on his behalf, something that was well within his power on many occasions.[25]

Former president Millard Fillmore's "Know-Nothing" candidacy helped Buchanan defeat John C. Frémont, the first Republican candidate for president in 1856. He served as president from March 4, 1857, to March 4, 1861. President-elect Buchanan stated about the growing schism in the country: "The object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union under a national and conservative government."[26] He set about this initially by maintaining a sectional balance in his appointments and persuading the people to accept constitutional law as the Supreme Court interpreted it. The court was considering the legality of restricting slavery in the territories and two justices had hinted to Buchanan their findings.[27]

Buchanan was the last president born in the 18th century and, at age 65, was the second-oldest man to be elected President at that time.

Presidency (1857–1861)

editDred Scott case

editIn his inaugural address, besides promising not to run again, Buchanan referred to the territorial question as "happily, a matter of but little practical importance" since the Supreme Court was about to settle it "speedily and finally", and proclaimed that when the decision came, he would "cheerfully submit, whatever this may be". Two days later, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, asserting that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories. Such comments delighted Southerners and incited anger in the North.[28]

Buchanan preferred to see the territorial question resolved by the Supreme Court. He had written to Justice John Catron in January 1857, inquiring about the outcome of the case and suggesting that a broader decision would be more prudent.[29] Catron, who was from Tennessee, replied on February 10 that the Supreme Court's southern majority would decide against Scott, but would likely have to publish the decision on narrow grounds if there was no support from the Court's northern justices—unless Buchanan could convince his fellow Pennsylvanian, Justice Robert Cooper Grier, to join the majority.[30][31] Buchanan then wrote to Grier and successfully prevailed upon him, allowing the majority leverage to issue a broad-ranging decision that transcended the specific circumstances of Scott's case to declare the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional.[32][33] The correspondence was not public at the time; however, at his inauguration, Buchanan was seen in whispered conversation with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. When the decision was issued two days later, Republicans began spreading word that Taney had revealed to Buchanan the forthcoming result.[33] Abraham Lincoln, in his 1858 House Divided Speech, denounced Buchanan, Taney, Stephen A. Douglas and Franklin Pierce as accomplices of the Slave Power, a supposed oligarchy aiming to eliminate legal barriers to slavery.[34]

Chaos in Kansas; Buchanan breaks with Douglas

editThe Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 created Kansas Territory, and allowed the settlers there to choose whether to allow slavery. This resulted in violence between "Free-Soil" (antislavery) and proslavery settlers in what became known as the "Bleeding Kansas" crisis. The antislavery settlers organized a government in Topeka, while proslavery settlers established a seat of government in Lecompton, Kansas. For Kansas to be admitted to statehood, a state constitution had to be submitted to Congress with the approval of a majority of residents.

Toward this end, Buchanan appointed Robert J. Walker to replace John W. Geary as territorial governor, with the mission of reconciling the settler factions and approving a constitution, in May 1857. Walker, who was from Mississippi, was expected to assist the proslavery faction in gaining approval of their Lecompton Constitution. However, most Kansas settlers were Free-Soilers. The Lecomptonites held a referendum, which Free-Soilers boycotted, with trick terms and claimed their constitution was adopted. Walker resigned in disgust.[35]

Nevertheless, Buchanan now pushed for congressional approval of Kansas statehood under the Lecompton Constitution. Buchanan made every effort to secure congressional approval, offering favors, patronage appointments, and even cash for votes.[36] The Lecompton bill passed through the House of Representatives, but failed in the Senate, where it was opposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, leader of the northern Democrats. Douglas advocated "popular sovereignty" (letting settlers decide on slavery—nicknamed "squatter sovereignty" by Douglas' opponents); he rejected the fraudulent way the Lecompton Constitution was supposedly adopted.[37]

The battle over Kansas escalated into a battle for control of the Democratic Party. On one side were Buchanan, most Southern Democrats, and northern Democrats allied to the Southerners ("Doughfaces"); on the other side were Douglas and most northern Democrats plus a few Southerners. The struggle lasted from 1857 to 1860. Buchanan used his patronage powers to remove Douglas' sympathizers in Illinois and Washington, DC and installed proadministration Democrats, including postmasters.[38]

Douglas's Senate term ended in 1859, so the Illinois legislature elected in 1858 had to choose whether to re-elect him. The Senate choice was the primary issue of the legislative election, marked by the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. Buchanan, working through Federal patronage appointees in Illinois, ran candidates for the legislature in competition with both the Republicans and the Douglas Democrats. This could easily have thrown the election to the Republicans—which showed the depth of Buchanan's animosity toward Douglas.[39] In the end, however, Douglas Democrats won the legislative election and Douglas was re-elected to the Senate. Douglas forces took control throughout the North, except in Buchanan's home state of Pennsylvania. Buchanan was reduced to a narrow base of southern supporters.[35][40]

Panic of 1857

editThe Panic of 1857 began in the summer of that year, brought on mostly by the people's overconsumption of goods from Europe to such an extent that the Union's specie was drained off, overbuilding by competing railroads, and rampant land speculation in the west. Most of the state banks had overextended credit, to more than $7.00 for each dollar of gold or silver. The Republicans considered the Congress to be the culprit for having recently reduced tariffs.

Buchanan's response, outlined in his first Annual Message to Congress, was "reform not relief". While the government was "without the power to extend relief",[41] it would continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail public works, none would be added. He urged the states to restrict the banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie, and discouraged the use of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. The economy did eventually recover, though many Americans suffered as a result of the panic.[42] The South, due to an agriculture-based economy, was considered to have been less severely affected than the North, where manufacturers were hit hardest. Buchanan, by the time he left office in 1861, had accumulated a federal deficit of $17 million.[41]

Utah War

editIn March 1857, Buchanan received conflicting reports from federal judges in the Utah Territory that their offices had been disrupted and they had been driven from their posts by the Mormons. He knew that the Pierce administration had refused to facilitate Utah being granted statehood and the Mormons feared the loss of their property rights. Accepting the wildest rumors and believing the Mormons to be in open rebellion against the United States, Buchanan sent the Army in November of that year to replace Brigham Young as governor with the non-Mormon Alfred Cumming. While the Mormons' defiance of federal authority in the past had become traditional, some question whether Buchanan's action was a justifiable or prudent response to uncorroborated reports.[28] Complicating matters, Young's notice of his replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had annulled the Utah mail contract.[28] After Young reacted to the military action by mustering a two-week expedition destroying wagon trains, oxen, and other Army property, Buchanan dispatched Thomas L. Kane as a private agent to negotiate peace. The mission succeeded, the new governor was shortly placed in office, and the Utah War ended. The President granted amnesty to all inhabitants who would respect the authority of the government, and moved the federal troops to a nonthreatening distance for the balance of his administration.[43]

Partisan deadlock

editThe division between northern and southern Democrats allowed the Republicans to win a plurality in the House in the election of 1858. Their control of the chamber allowed the Republicans to block most of Buchanan's agenda (including his proposals for expansion of influence in Central America, and for the purchase of Cuba). Buchanan thought the ideologies of the United States would bring peace and prosperity to these neighboring lands as they had in the Northwest and that without U.S. influence, the major European powers would intervene. The imperative of safe and speedy travel from east to west was of strategic importance to the country. These goals would not be reached. Buchanan, in turn, vetoed six substantial pieces of Republican legislation, causing further hostility between Congress and the White House.[44]

Covode committee

editIn March 1860, the House created the Covode committee to investigate the administration for evidence of offenses, some impeachable, such as bribery and extortion of representatives in exchange for their votes. The committee, with three Republicans and two Democrats, was accused by Buchanan's supporters of being nakedly partisan; they also charged its chairman, Republican Rep. John Covode, with acting on a personal grudge (since the president had vetoed a bill that was fashioned as a land grant for new agricultural colleges, but was designed to benefit Covode's railroad company[45]). However, the Democratic committee members, as well as Democratic witnesses, were equally enthusiastic in their pursuit of Buchanan, and as pointed in their condemnations, as the Republicans.[46][47]

The committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan; however, the majority report issued on June 17 exposed corruption and abuse of power among members of his cabinet, as well as allegations (if not impeachable evidence) from the Republican members of the Committee, that Buchanan had attempted to bribe members of Congress in connection with the Lecompton constitution. (The Democratic report, issued separately the same day, pointed out that evidence was scarce, but did not refute the allegations; one of the Democratic members, Rep. James Robinson, stated publicly that he agreed with the Republican report even though he did not sign it.[47])

Buchanan claimed to have "passed triumphantly through this ordeal" with complete vindication. Nonetheless, Republican operatives distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report throughout the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election.[48][49]

Disintegration: Election of 1860

editSectional strife rose to such a pitch that the Democratic Party's national convention in 1860 led directly to a schism in the Party. Buchanan played little part at the national convention, meeting in Charleston, South Carolina. The southern wing walked out of the convention and nominated its own candidate for the presidency, incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge. Another faction nominated former Speaker of the House John Bell, who took no position on slavery; his only focus was on saving the Union. The remainder of the party finally nominated Buchanan's archenemy, Stephen Douglas. For his part, President Buchanan supported Breckinridge's candidacy. When the Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln, it was a near certainty that he would be elected.

As early as October, the army's Commanding General, Winfield Scott, warned Buchanan that Lincoln's election would likely cause at least seven states to secede. He also recommended to Buchanan that massive amounts of federal troops and artillery be deployed to those states to protect federal property, although he also warned that few reinforcements were available (Congress had since 1857 failed to heed both men's calls for a stronger militia and had allowed the Army to fall into deplorable condition.[50]) Buchanan, however, distrusted Scott (the two had long been political adversaries) and ignored his recommendations.[51] After Lincoln's election, Buchanan directed War Secretary Floyd to reinforce southern forts with such provisions, arms and men as were available; however, Floyd convinced him to revoke the order.[50]

With Lincoln's victory, talk of secession and disunion reached a boiling point. Buchanan was forced to address it in his final message to Congress. Both factions awaited news of how Buchanan would deal with the question. In his message,[52] Buchanan denied the legal right of states to secede but held that the federal government legally could not prevent them. He placed the blame for the crisis solely on "intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the Southern States", and suggested that if they did not "repeal their unconstitutional and obnoxious enactments ... the injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union."[53] Buchanan's only suggestion to solve the crisis was "an explanatory amendment" reaffirming the constitutionality of slavery in the states, the fugitive slave laws, and popular sovereignty in the territories.[53] His address was sharply criticized both by the north, for its refusal to stop secession, and the south, for denying its right to secede.[54] Five days after the address was delivered, Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb resigned, feeling that his views and the President's had become irreconcilable.[55]

Efforts were made by statesmen such as Sen. John J. Crittenden, Rep. Thomas Corwin, and former president John Tyler to negotiate a compromise to stop secession, with Buchanan's support; all failed. Failed efforts to compromise were also made by a group of governors meeting in New York. Buchanan employed a last-minute tactic, in secret, to bring a solution. He attempted in vain to procure President-elect Lincoln's call for a constitutional convention or national referendum to resolve the issue of slavery. Lincoln declined.[56]

South Carolina declared its secession on December 20, 1860, followed by six other slave states, and, by February 1861, they had formed the Confederate States of America. As Scott had surmised, the secessionist governments declared eminent domain over federal property within their states; Buchanan and his administration took no action to stop the confiscation of government property.

Beginning in late December, Buchanan reorganized his cabinet, ousting Confederate sympathizers and replacing them with hard-line nationalists Jeremiah S. Black, Edwin M. Stanton, Joseph Holt and John A. Dix. These conservative Democrats strongly believed in American nationalism and refused to countenance secession. At one point, Treasury Secretary Dix ordered Treasury agents in New Orleans, "If any man pulls down the American flag, shoot him on the spot." The new cabinet advised Buchanan to request from Congress the authority to call up militias and give himself emergency military powers, and this he did, on January 8, 1861. Nevertheless, by that time Buchanan's relations with Congress were so strained that his requests were rejected out of hand. Many consider him as the worst President in history for his failure to prevent the American Civil War.[57][58][59][60]

Fort Sumter

editBefore Buchanan left office, all arsenals and forts in the seceding states were lost (except Fort Sumter, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, and three island outposts in Florida), and a fourth of all federal soldiers surrendered to the Texas militia. Knowing that secessionist fervor was strongest in South Carolina, Buchanan made a quiet pact with South Carolina's legislators that he would not reinforce the Charleston garrison in exchange for no interference from the state.[61] However, Buchanan did not inform the Charleston commander, Major Robert Anderson, of the agreement, and on December 26 Anderson violated it by moving his command to Fort Sumter. Southerners responded with a demand that Buchanan remove Anderson, while northerners demanded support for the commander. On December 31, in an apparent panic and without consulting Anderson, Buchanan ordered reinforcements.[61]

On January 5, Buchanan sent civilian steamer Star of the West to carry reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter, which, located in Charleston harbor, was a conspicuously visible spot in the Confederacy. On January 9, 1861, South Carolina state batteries opened fire on the ship, causing it to withdraw and return to New York. Buchanan was again criticized by both north (for lack of retaliation against the hostile South Carolina batteries) and south (for attempting to reinforce Fort Sumter), further alienating both factions.[61][62] Paralyzed, Buchanan made no further moves either to prepare for war or to avert it.

On Buchanan's final day as president, March 4, 1861, he remarked to the incoming Lincoln, "If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man."[63]

Presidential cabinet

editFrom left to right: Jacob Thompson, Lewis Cass, John B. Floyd, James Buchanan, Howell Cobb, Isaac Toucey, Joseph Holt and Jeremiah S. Black, (c. 1859)

Judicial appointments

editBuchanan appointed one Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, Nathan Clifford. Buchanan appointed only seven other Article III federal judges, all to United States district courts. He also appointed two Article I judges to the United States Court of Claims.

States admitted to the Union

editPolitical views

editBuchanan considered the essence of good self-government to be founded on restraint. The constitution he considered to be "...restraints, imposed not by arbitrary authority, but by the people upon themselves and their representatives.... In an enlarged view, the people's interests may seem identical, but "to the eye of local and sectional prejudice, they always appear to be conflicting ... and the jealousies that will perpetually arise can be repressed only by the mutual forbearance which pervades the constitution."[64]

One of the greatest issues of the day was tariffs. Buchanan condemned both free trade and prohibitive tariffs, since either would benefit one section of the country to the detriment of the other. As the senator from Pennsylvania, he thought: "I am viewed as the strongest advocate of protection in other states, whilst I am denounced as its enemy in Pennsylvania."[65]

Buchanan, like many of his time, was torn between his desire to expand the country for the benefit of all and his insistence on guaranteeing to the people settling the expanded areas their rights, including slavery. On territorial expansion, he said, "What, sir? Prevent the people from crossing the Rocky Mountains? You might just as well command the Niagara not to flow. We must fulfill our destiny."[66] On the resulting spread of slavery, through unconditional expansion, he stated: "I feel a strong repugnance by any act of mine to extend the present limits of the Union over a new slave-holding territory." For instance, he hoped the acquisition of Texas would "be the means of limiting, not enlarging, the dominion of slavery".[66]

Nevertheless, in deference to the intentions of the typical slaveholder, he was quick to provide the benefit of much doubt. In his third annual message, Buchanan claimed that the slaves were "treated with kindness and humanity.... Both the philanthropy and the self-interest of the master have combined to produce this humane result."[67]

Historian Kenneth Stampp wrote: "Shortly after his election, he assured a southern Senator that the "great object" of his administration would be "to arrest, if possible, the agitation of the Slavery question in the North and to destroy sectional parties. Should a kind Providence enable me to succeed in my efforts to restore harmony to the Union, I shall feel that I have not lived in vain." In the northern anti-slavery idiom of his day, Buchanan was often considered a "doughface", a northern man with southern principles.[68]

The President, however, also felt that "this question of domestic slavery is the weak point in our institutions, touch this question seriously ... and the Union is from that moment dissolved. Although in Pennsylvania we are all opposed to slavery in the abstract, we can never violate the constitutional compact we have with our sister states. Their rights will be held sacred by us. Under the constitution it is their own question; and there let it remain."[69]

Buchanan was irked that the abolitionists, in his view, were preventing the solution to the slavery problem. He stated, "Before [the abolitionists] commenced this agitation, a very large and growing party existed in several of the slave states in favor of the gradual abolition of slavery; and now not a voice is heard there in support of such a measure. The abolitionists have postponed the emancipation of the slaves in three or four states for at least half a century."[69]

Buchanan greatly valued education, but believed that colleges were the duty of state governments rather than the central government, as expressed in his veto of a bill to grant land for colleges.

"It is extremely doubtful, to say the least, whether this bill would contribute to the advancement of agriculture and the mechanic arts—objects the dignity and value of which can not be too highly appreciated."

"The Federal Government, which makes the donation, has confessedly no constitutional power to follow it into the States and enforce the application of the fund to the intended objects. As donors we shall possess no control over our own gift after it shall have passed from our hands. It is true that the State legislatures are required to stipulate that they will faithfully execute the trust in the manner prescribed by the bill. But should they fail to do this, what would be the consequence? The Federal Government has no power, and ought to have no power, to compel the execution of the trust."

Near the end of his administration, he had a serious exchange with the Rev. William Paxton. After what Paxton described as quite a probative discussion, Buchanan said, " Well, sir ... I hope I am a Christian. I have much of the experience you have described, and as soon as I retire, I will unite with the Presbyterian Church." Paxton asked why he delayed, to which he replied, "I must delay for the honor of religion. If I were to unite with the church now, they would say 'hypocrite' from Maine to Georgia."[70]

Final years

editThe Civil War erupted within two months of Buchanan's retirement. He supported the United States, writing to former colleagues that "the assault upon Sumter was the commencement of war by the Confederate states, and no alternative was left but to prosecute it with vigor on our part".[71] He also wrote a letter to his fellow Pennsylvania Democrats, urging them to "join the many thousands of brave & patriotic volunteers who are already in the field".[71]

However, Buchanan spent most of his remaining years defending himself from public blame for the Civil War, which was even referred to by some as "Buchanan's War".[71] He began receiving angry and threatening letters daily, and stores displayed Buchanan's likeness with the eyes inked red, a noose drawn around his neck and the word "TRAITOR" written across his forehead. The Senate proposed a resolution of condemnation which ultimately failed, and newspapers accused him of colluding with the Confederacy. His former cabinet members, five of whom had been given jobs in the Lincoln administration, refused to defend Buchanan publicly.[72]

Initially so disturbed by the attacks that he fell ill and depressed, Buchanan finally began defending himself in October 1862, in an exchange of letters between himself and Winfield Scott that was published in the National Intelligencer newspaper.[73] He soon began writing his fullest public defense, in the form of his memoir Mr. Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of Rebellion, which was published in 1866.

Buchanan caught a cold in May 1868, which quickly worsened due to his advanced age. He died on June 1, 1868, from respiratory failure at the age of 77 at his home at Wheatland and was interred in Woodward Hill Cemetery in Lancaster.

Personal life

editIn 1818, Buchanan met Anne Caroline Coleman at a grand ball at Lancaster's White Swan Inn, and the two began courting. Anne was the daughter of the wealthy iron manufacturing businessman (and protective father) Robert Coleman and sister-in-law of Philadelphia judge Joseph Hemphill, one of Buchanan's colleagues from the House of Representatives. By 1819, the two were engaged, but could spend little time together; Buchanan was extremely busy with his law firm and political projects during the Panic of 1819, which took him away from Coleman for weeks at a time. Conflicting rumors abounded, suggesting that he was marrying her for her money, because his own family was less affluent, or that he was involved with other women. Buchanan never publicly spoke of his motives or feelings, but letters from Anne revealed she was paying heed to the rumors.[74]

After Buchanan visited a friend's wife, Coleman broke off the engagement. She died suddenly soon afterward, on December 9, 1819. The records of a Dr. Chapman, who looked after her in her final hours, and who commented just after her death that it was "the first instance he ever knew of hysteria producing death", reveal that he theorized, despite the absence of any valid evidence, that she had overdosed on laudanum, a concentrated tincture of opium.[75] In a letter to her father, he asked to attend the funeral, and wrote that "I feel happiness has fled from me forever";[76] Coleman's father refused permission.[77]

After Coleman's death, Buchanan never courted another woman or seemed to show any emotional or physical interest; a rumor circulated of an affair with President James K. Polk's widow, Sarah Childress Polk, but it had no basis.[78] It has been suggested that Anne's death in fact served to deflect awkward questions about his sexuality and bachelorhood.[76] While his biographers such as Jean Baker argue that Buchanan was asexual or celibate,[79] several writers have put forth arguments that he was homosexual or bisexual, including sociologist James W. Loewen,[80] and authors Robert P. Watson and Shelley Ross.[81][82]

A source of this interest has been Buchanan's close and intimate relationship with William Rufus King (who became Vice President under Franklin Pierce). The two men lived together in a Washington boardinghouse for 10 years from 1834 until King's departure for France in 1844. King referred to the relationship as a "communion",[78] and the two attended social functions together. Contemporaries also noted the closeness. Andrew Jackson called them "Miss Nancy" and "Aunt Fancy" (the former being a 19th-century euphemism for an effeminate man[83]), while Aaron V. Brown referred to King as Buchanan's "better half".[84] James W. Loewen described Buchanan and King as "Siamese twins". In later years, Catherine Thompson, the wife of cabinet member Jacob Thompson, expressed her anxiety that "there was something unhealthy in the president's attitude".[78]

Buchanan adopted King's mannerisms and romanticized view of southern culture. Both had strong political ambitions, and in 1844 they planned to run as president and vice president. Author Robert Thompson described them both as soft, effeminate, and eccentric.[78] In May 1844, Buchanan wrote to Cornelia Roosevelt, "I am now 'solitary and alone', having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone, and [I] should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection."[78]

King became ill in 1853 and died of tuberculosis shortly after Pierce's inauguration, four years before Buchanan became President. Buchanan described him as "among the best, the purest and most consistent public men I have known."[78] While author Jean Baker indicated in her biography of Buchanan that his and King's nieces may have destroyed some correspondence between Buchanan and King, she also stated that the length and intimacy of their surviving letters illustrate only "the affection of a special friendship."[85]

During Buchanan's presidency, his orphaned niece, Harriet Lane, whom he had adopted, served as official White House hostess.[86]

Legacy

editThe day before his death, Buchanan predicted that "history will vindicate my memory".[87] Historians have defied that prediction and criticize Buchanan for his unwillingness or inability to act in the face of secession. Historical rankings of United States Presidents, considering presidential achievements, leadership qualities, failures and faults, consistently place Buchanan among the least successful presidents.[88][89] When scholars are surveyed he ranks close to the bottom in terms of vision/agenda-setting, domestic leadership, foreign policy leadership, moral authority and positive historical significance of their legacy.[90]

Buchanan biographer Philip Klein explains the challenges Buchanan faced:

Buchanan assumed leadership ... when an unprecedented wave of angry passion was sweeping over the nation. That he held the hostile sections in check during these revolutionary times was in itself a remarkable achievement. His weaknesses in the stormy years of his presidency were magnified by enraged partisans of the North and South. His many talents, which in a quieter era might have gained for him a place among the great presidents, were quickly overshadowed by the cataclysmic events of civil war and by the towering Abraham Lincoln."[91]

Buchanan never had a strong reputation. Years before Buchanan won the White House, President James K. Polk confided to his diary: "Mr. Buchanan is an able man, but is in small matter without judgment and sometimes acts like an old maid."[92] The National Intelligencer, a leading opposition newspaper, ridiculed Buchanan on January 24, 1859, for his follies as president, citing a series of his "magnificent" proposals that all failed:

We must retrench the extravagant list of magnificent schemes which received the sanction of the Executive ... the great Napoleon himself, with all the resources of an empire at his sole command, never ventured the simultaneous accomplishments of so many daring projects. The acquisition of Cuba ... ; the construction of a Pacific Railroad ... ; a Mexican protectorate, the international preponderance in Central America, in spite of all the powers of Europe; the submission of distant South American states; ... the enlargement of the Navy; a largely increased standing Army ... what government on earth could possibly meet all the exigencies of such a flood of innovations?[93]

Buchanan is remembered today for other missed opportunities rather than any significant accomplishments. He vetoed the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both of which Lincoln signed into law only a few years later; the Homestead Act accelerated westward expansion, while the Morrill Act accelerated agricultural and engineering research and education to develop the young nation.

A bronze and granite memorial residing near the southeast corner of Washington, D.C.'s Meridian Hill Park was designed by architect William Gorden Beecher and sculpted by Maryland artist Hans Schuler. Commissioned in 1916 but not approved by the U.S. Congress until 1918, and not completed and unveiled until June 26, 1930, the memorial features a statue of Buchanan bookended by male and female classical figures representing law and diplomacy, with the engraved text reading: "The incorruptible statesman whose walk was upon the mountain ranges of the law", a quote from a member of Buchanan's cabinet, Jeremiah S. Black.

The memorial in the nation's capital complemented an earlier monument, constructed in 1907–08 and dedicated in 1911, on the site of Buchanan's birthplace in Stony Batter, Pennsylvania.[94] Part of the original 18.5-acre (75,000 m2) memorial site is a 250-ton pyramid structure which stands on the site of the original cabin where Buchanan was born. The monument was designed to show the original weathered surface of the native rubble and mortar.

Three counties are named in his honor: Buchanan County, Iowa, Buchanan County, Missouri, and Buchanan County, Virginia. Another in Texas was christened in 1858 but renamed Stephens County, after the newly elected Vice President of the Confederate States of America, Alexander Stephens, in 1861.[95] The city of Buchanan, Michigan was also named after him.[96]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Klein 1962, p. 305.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. xviii.

- ^ U.S. historians pick top 10 presidential errors en Wayback Machine (archivado el 24 de June de 2006).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Buchanan Family 1430 – 1903". ancestry.com. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "The James Buchanan Hotel, Pub & Restaurant – A Brief History". Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Horton, Rushmore G. (1856). The Life and Public Services of James Buchanan. New York, NY: Derby & Jackson. p. 17.

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Buchanan, James; Moore, John Bassett, editor (1911). The Works of James Buchanan. Vol. 12. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Company. p. 294.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cadwalader, John (1895). The Constitution and Register of Membership of the General Society of the War of 1812 to December 1, 1895. Dewey & Eakins: Philadelphia, PA. p. 65.

- ^ O'Brien, Marco. "Military trivia facts". Military.com. Military Advantage, a division of Monster Worldwide. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

Only one President (James Buchanan) served as an enlisted man in the military and did not go on to become an officer.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 27.

- ^ Curtis 1883, p. 22.

- ^ Curtis 1883, pp. 107–109.

- ^ "US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations: About the Committee – History". United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 170.

- ^ Seigenthaler 2004, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 210.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 415.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McPherson 1988, p. 110.

- ^ Tucker 2009, pp. 456–57.

- ^ Sandburg, Carl; Goodman, Edward C. (2007). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. New York, NY: Sterling Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4027-4288-0.

- ^ Passages From the English Note-Books of Nathaniel Hawthorne, edited by Sophia Hawthorne; Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1870; entry for January 6, 1855.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 248–252.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Klein 1962, p. 316.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Hall 2001, p. 566.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Armitage et al. 2005, p. 388.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baker 2004, p. 85.

- ^ "A House Divided (final paragraph)". Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Potter 1976, pp. 297–327.

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 91.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 286–299.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baker 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 317.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 312.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 338.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 338–9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grossman 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 339.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Klein 1962, pp. 356–358.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 76, 133.

- ^ "James Buchanan, Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, December 3, 1860". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Buchanan (1860)

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 363.

- ^ "The Resignation of Secretary Cobb. The Correspondence". The New York Times. December 14, 1860.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 381–387.

- ^ Silver, Nate (January 23, 2013). "Contemplating Obama's Place in History, Statistically". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Lind, Michael (December 3, 2006). "He's Only Fifth Worst". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (July 1, 2013). "James Buchanan: Worst US president?". BBC News, Washington. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Dunbar, Elizabeth (February 19, 2006). "James Buchanan worst president, scholars say". Pocono News. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "James Buchanan's Activist Blunder". The New York Times. January 5, 2011.

- ^ "James Buchanan – Fort sumter". Profiles of U. S. Presidents. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 140.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 143.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Klein 1962, p. 147.

- ^ "Third Annual Message (December 19, 1859)". The Miller Center at the University of Virginia. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Stampp 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Klein 1962, p. 150.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Birkner, Michael (September 20, 2005). "Buchanan's Civil War". Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 408–413.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 417–418.

- ^ Boertlein, John (2010). Presidential Confidential: Sex, Scandal, Murder and Mayhem in the Oval Office. Cincinnati, OH: Clerisy Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-57860-361-9.

- ^ Klein 1955.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Charles Dunn, The scarlet thread of scandal: Morality and the American presidency, Maryland, 2001

- ^ Sandburg, Carl (1939). Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & Company. p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Template:Harvnb[page needed]

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Loewen, Jim (May 14, 2012). "Our real first gay president". Salon. Salon Media Group, Inc. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Ross 1988, pp. 86–91: Today there is evidence that President James Buchanan was a homosexual.

- ^ Watson 2012, p. 233.

- ^ The Wordsworth Book of Euphemisms by Judith S. Neaman and Carole G. Silver (Wordsworth Editions Ltd., Hertfordshire)

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Harriet Lane". The White House – Our First Ladies. The White House. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ "Buchanan's Birthplace State Park". Pennsylvania State Parks. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ Tolson, Jay (February 16, 2007). "The 10 Worst Presidents". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Hines, Nico (October 28, 2008). "The 10 worst presidents to have held office". The Times. London. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ "The top US presidents: First poll of UK experts". BBC News. January 17, 2011.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 429.

- ^ James K. Polk, Polk: The Diary of a President 1845–1849, ed. Allan Nevins (London: Longmans, Green, 1929, p. 355 (February 27, 1849), quoted in Walter R. Borneman, Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. New York: Random House, 2008 ISBN 978-1-4000-6560-8, p. 335.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, pp. 251–52.

- ^ "Buchanan's Birthplace State Park". Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Beatty 2001, p. 310.

- ^ Hoogterp, Edward (2006). West Michigan Almanac, p. 168. The University of Michigan Press & The Petoskey Publishing Company.

Bibliography

edit- Baker, Jean H. (2004). James Buchanan. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8050-6946-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) excerpt and text search - Curtis, George Ticknor (1883). Life of James Buchanan: Fifteenth President of the United States. Vol. 2. Harper & Brothers.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) [1] [2] - Klein, Philip S. (1962). President James Buchanan: A Biography (1995 ed.). Newtown, Connecticut: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 0-945707-11-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nevins, Allan (1950). The Emergence of Lincoln: Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857–1859. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684104157.

- Potter, David Morris (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060905248.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Pulitzer prize. - Rhodes, James Ford (1906). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the End of the Roosevelt Administration. Vol. 2. Macmillan.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (1990). America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195074819.

- Watson, Robert P. (2012). Affairs of State: The Untold History of Presidential Love, Sex, and Scandal, 1789–1900. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442218369.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743902.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099528.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burrs, Charles Thomas (1967). M.A. Thesis: James Buchanan's Diplomatic Mission to England, 1853–1856. University of Delaware.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chadwick, Bruce (2008). 1858: Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant and the War They Failed to See. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 140220941X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court justices: a biographical dictionary. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Armitage, Susan H.; Faragher, John Mack; Buhle, Mari Jo; Czitrom, Daniel J. (2005). Out of Many, TLC Combined, Revised Printing (4th Edition). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-195130-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grossman, Mark (2003). Political Corruption in America: An Encyclopedia of Scandals, Power, and Greed. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-060-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ross, Shelley (1988). Fall from Grace: Sex, Scandal, and Corruption in American Politics from 1702 to the Present. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-35381-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beatty, Michael A. (2001). County Name Origins of the United States. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1025-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klein, Philip Shriver (December 1955). "The Lost Love of a Bachelor President". American Heritage Magazine. 7 (1). Retrieved November 29, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Primary sources

- Buchanan, James. Fourth Annual Message to Congress. (1860, December 3).

- Buchanan, James. Mr Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (1866)

- National Intelligencer (1859)

Further reading

edit- Binder, Frederick Moore. "James Buchanan: Jacksonian Expansionist" Historian 1992 55(1): 69–84. ISSN 0018-2370 Full text: in Ebsco

- Binder, Frederick Moore. James Buchanan and the American Empire. Susquehanna U. Press, 1994.

- Birkner, Michael J., ed. James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s. Susquehanna U. Press, 1996.

- Boulard, Garry. The Worst President--The Story of James Buchanan iUniverse, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4917-5961-5.

- Meerse, David. "Buchanan, the Patronage, and the Lecompton Constitution: a Case Study" Civil War History 1995 41(4): 291–312. ISSN 0009-8078

- Nevins, Allan. The Emergence of Lincoln 2 vols. (1960) highly detailed narrative of his presidency

- Nichols, Roy Franklin; The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854 (1923), detailed narrative; online

- Quist, John W. and Birkner, Michael J. (eds.), james Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2013.

- Rhodes, James Ford History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 vol 2. (1892)

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. Wiley. pp 397–464

- Smith, Elbert B. The Presidency of James Buchanan (1975). ISBN 0-7006-0132-5, standard history of his administration

- Updike, John Buchanan Dying: A Play (1974). ISBN 0-394-49042-8, ISBN 0-8117-0238-3, containing an 80-page historical "Afterword" that discusses sources, etc.

External links

edit- 20x15px|link=|alt= Wikiquote alberga frases célebres de o sobre James Buchanan.

- United States Congress. "James Buchanan (id: B001005)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Buchanan: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Biography of James Buchanan (Official White House site)

- The James Buchanan papers, spanning the entirety of his legal, political and diplomatic career, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- University of Virginia article: Buchanan biography

- Wheatland

- James Buchanan at Tulane University

- Essay on James Buchanan and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Buchanan's Birthplace State Park, Franklin County, Pennsylvania

- "Life Portrait of James Buchanan", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, June 21, 1999

- Primary sources

- Script error: No such module "Gutenberg".

- Works by or about James Buchanan at Internet Archive

- James Buchanan Ill with Dysentery Before Inauguration: Original Letters Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Mr. Buchanans Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. President Buchanans memoirs.

- Inaugural Address

- Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1860